Translator: Andrés Fernando Cardona Ramírez

Spanish version: http://www.elcolombiano.com/blogs/lacajaregistradora/?p=1420

The twentieth century was largely a protectionist century. In this context, Latin American countries, including Colombia, conducted an import substitution policy seeking to promote the nascent industry. In the 1960s, this policy was supplemented by export promotion strategies to diversify the offer and sell the world other goods than mining and agriculture.

However, for emerging economic trends in late twentieth century, to the academy and to those in power, the ECLAC economic model ran out. In its place, neoliberalism substantiated opening strategies to modernize the economy, liberalizing trade and attracting foreign investment. However, a quarter century later, there are reasons to wonder where Colombia is going in terms of economic development.

Expectations:

The twentieth century protectionist model gave way to a significant light industry, with progress in production of household appliances, electrical instruments and vehicle assembly. Parallel to this, exports diversified, reducing dependency on coffee and increasing the production of other goods, especially in the agribusiness and textile sectors. However, the paradigm of competitive advantage was imposed on the world; therefore, the door was opened to competition, new suppliers and investors to create conditions for modernizing the economy.

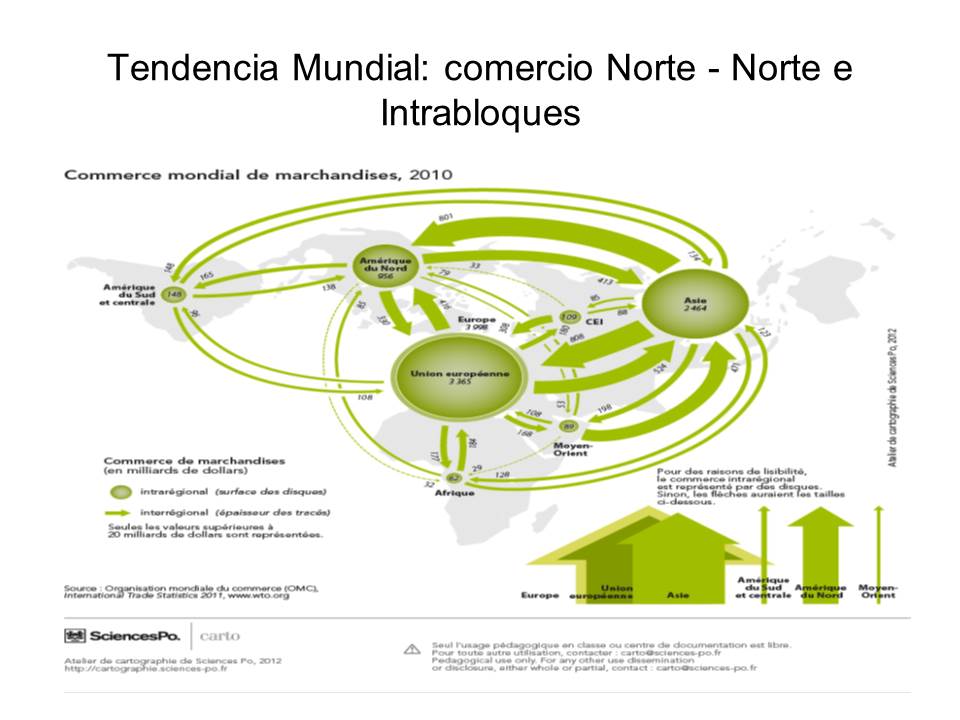

As shown on the map of Sciences Po, most world trade is within the North blocks (circles) and between them (thick arrows). This is because they involve manufactured products with high level of technological sophistication, and in these, few Latin circuits are involved, Colombia included: we must create competitive advantage.

Consequently, from the beginning, economic liberalization was expected to make foreign investment modernize our production, make our production more sophisticated, foreign competition would oblige our fledgling industry to get better in order to compete. these pillars expected to be the base for a new economy centered on the creation of competitive advantage for firms.

Reality

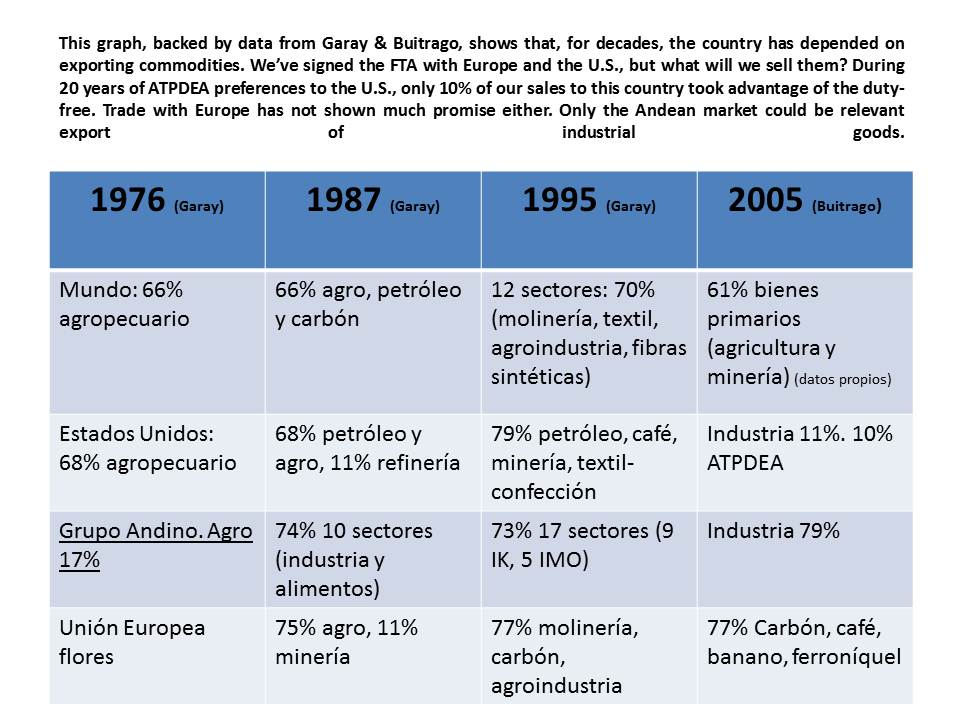

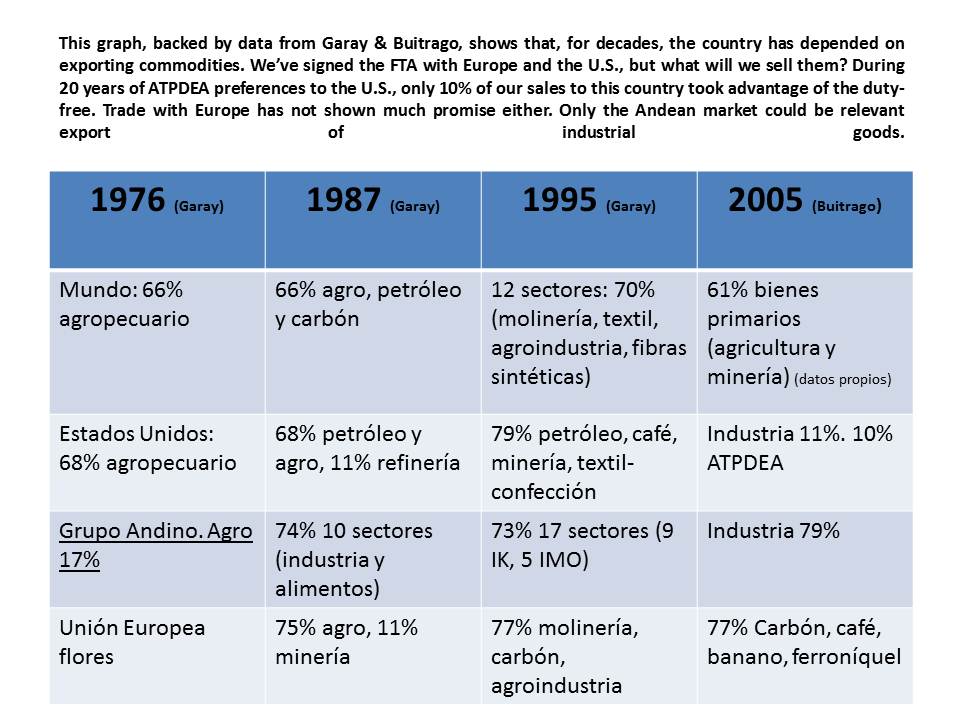

However, although some companies have modernized, overall figures indicate that Colombia does not advance in this direction. According to studies by the Bank of the Republic, until the beginning of economic liberalization (1990), coffee represented between 50 and 70% of exports. In the 1990s, exports other than coffee and oil and became almost 50% of the total export supply. But this does not mean that the manufacturing industry had been the major enhancer, although some of it if was: Venezuela was mainly, within the frame of CAN, a big market for assembled vehicles, apparel and agribusiness.

However, the balance of the first decade of the twenty first century states that what little progress had been made in diversification has been waning. While we do not depend significantly on coffee exports, unprocessed mining products have come to occupy this privileged position. Between oil, coal, ferronickel and gold do we find the axis of Colombian sales abroad, which are complemented by a light industry that does not evolve: apparel, bananas and flowers. According to the Private Competitiveness Council, 88% of our exports are raw materials or low-tech goods.

Consequently, we are in an ambiguous situation: we started a model of economic opening, inspired by the principles of Competitive Advantage, which means science, technology and innovation. But the sophistication of our industry and agriculture is not happening. We have better communications a more internationalized banking, higher education offer, but we still export raw goods. We are not doing something right.

Macroeconomics:

we have become a mining economy. Coal and oil have become our main source of foreign exchange, exports and attracting foreign investment. However, this situation is a determinant (while not exclusive) of the revaluation of the peso. Consequently, the mining boom is causing part of the weakness of other industries with aspirations to participate in international markets. The makers, flower coffee and banana growers lose competitiveness as a result of an unfavorable exchange rate. We are experiencing symptoms of Dutch disease. Is this sustainable?:

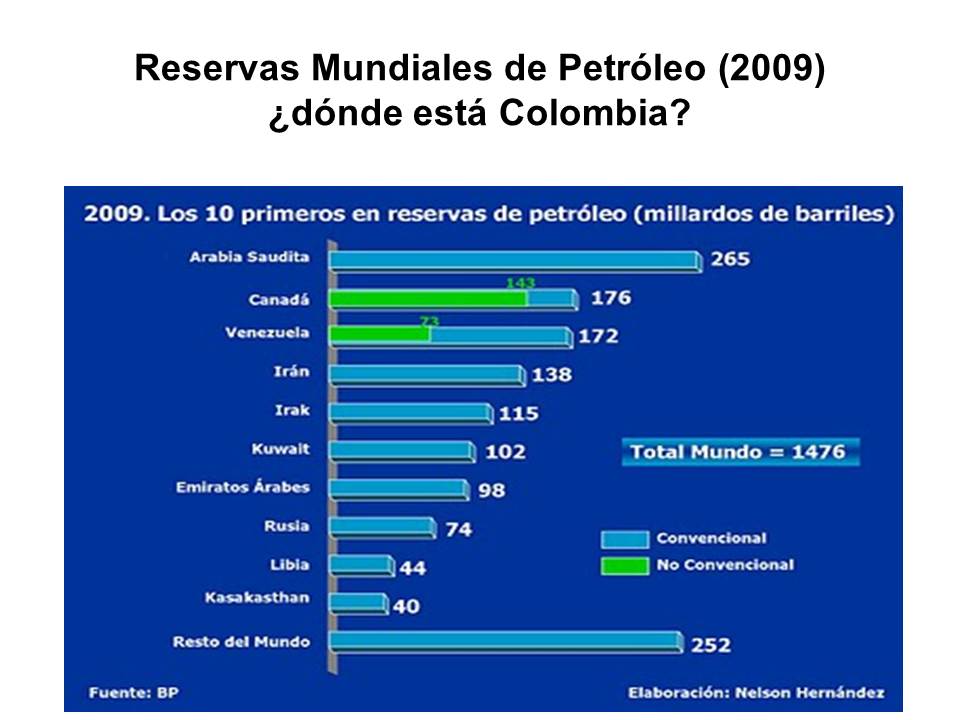

According to the data of the company BP, worked by Nelson Hernandez, 10 countries possess 80% of world oil reserves, but Colombia is not among them. Therefore, a mining development model, based on the oil industry does not seem sustainable in the long run for Colombia. There are no signs that we can sustain the long-term model derived from the investment currency and oil exports, while manufacturing and other industries, agricultural and depress as a result of the revaluation of the first causes.

Innovation and Sustainable Development:

the exchange rate is not the only thing that affects manufacturing and the agro Colombians. This country has very bad indicators for innovation, development, education and science. According to optimistic data, Colombia could be spending just under 0.5% of GDP on R & D processes, while successful East Asian countries are investing in this area about 4%. Neighbors such as Brazil and Chile, invest more than 1%. Our lack of vision translates into fewer patents and lower business innovation. It is no coincidence that one of the few companies that is patented in Colombia is Ecopetrol.

When it comes to education, although there are changes in the quantitative-more coverage, more masters, less illiteracy-, there are still significant shortcomings found in the qualitative: universities do little research and lack advancements in their approach to the big issues the country faces, particularly to the sophistication of our production capacity. There is little interest in the study of basic sciences and we are still seriously behind in bilingualism.

Finally, the country is having a big debate on mining. In this context there is serious concern about the poor relationship between the pursuit of a modern mining and sustainable development in Colombia: not only agriculture can be affected but, in general, it can cause irreparable environmental damage if the theme of “sustainable mining” is not clarified. Many interests are at stake and there is little legal and executive clarity .

To close:

while the present belongs to mining, the future is uncertain. Neither the economic liberalization started a quarter century ago, nor mining numbers are arguments to indicate that the country is headed in one direction or another. We are a rudderless ship signing FTA’s with everyone without thinking what it is that we will offer our partners in the future. As we have said in previous articles: to export hydrocarbons is not required to sign agreements … We have lost the compass!